Self-portrait, Helen Rousseau, c. 1920

Self-portrait, Helen Rousseau, c. 1920

The Paintings of Helen Rousseau, an informational site by her daughter Shirley Rousseau Murphy, part 2

Helen Rousseau

Laura Weir Hill and Scott Hill

From Art of California Magazine, November, 1991.

Copyright 1991 by Art Institute of California.

The leaders of Bay Area Figurative art created a movement that simultaneously extended and defied the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. Dozens of students at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA, now the San Francisco Art Institute) from 1950 to 1965 embraced the challenge defined by the movement's leaders David Park, Richard Diebenkorn, Elmer Bischoff, and James Weeks. That challenge was to accept the strength of Abstract Expressionism--its ability to make grand, personal statements--and to correct its perceived weaknesses, described by Park as the need for "the sting that a more descriptive reference to some fixed object can make." The result was, according to Carolyn Jones, a "union of figurative subject matter with Abstract Expressionist paint handling and formal compositional concerns."

The importance of the Bay Area Figurative Movement's originators and their most successful students has been well documented by the works of Paul Mills, Thomas Albright, and, most recently, Carolyn Jones. Yet, the full nature of the Bay Area Figurative Movement has not been fully explored. With the path paved by Mills. Albright, and Jones, attention now can turn to the movement's legacy as evident in succeeding generations of students at CSFA. This article is part of that process; it focuses on the career of Helen Rousseau, a first generation figurative student of Park at CSFA in 1951. Rousseau became connected with the Bay Area Figurative Movement by a circuitous route. During the first part of her career, she was a successful California Modernist, who painted local scenes and won regional awards. In her mid-fifties, she searched for another way to express herself and turned to painting in the figurative style.

Rousseau was born Helen Hoffman in Indiana in 1896. After her family relocated to Berkeley, Rousseau concentrated solely on training as a painter, leading her to study at Pomona College, UC Berkeley, and CSFA. In the 1925-26 academic year, she enrolled in courses taught by Gottardo Piazzoni, E. S. Macky, and Lee Randolph at CSFA. These artists provided an excellent foundation; however, it was another member of the faculty from whom Rousseau found the most guidance.

Otis Oldfield, who had recently returned from a lengthy stay in Paris, joined the faculty in the fall of 1925. Rousseau's daughter, Shirley Rousseau Murphy, recalls that her mother frequently accompanied Oldfield's classes on sketching trips in and around San Francisco. According to California Art Research, Oldfield was a successful teacher, who emphasized color zoning, the "reorganization of a surface into rhythm," and training the eye to impart disciplined contrast and construction. According to Thomas Albright in Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945-1980, "Oldfield transmitted to his students a fondness for heavily geometrisized, Cubist forms modeled on Cezanne." In an interview with Raymond L. Wilson, Nathan Oliviera remembers that Oldfield painted in a "crisply focused realist framework."

Between 1925 and 1950, Oldfield's influence is evident in Rousseau's work. Untitled Landscape is characteristic of her painting from this era, with form and contour conveyed through contrasting colors and geometric line. This is a classic American Scene composed in Rousseau's tight style.

Rousseau exhibited her paintings with many art associations including Women Painters of the West, which awarded her several first-place prizes in annual juried exhibits, the Whittier Art Association, the Artists Guild of Southern California, and the California Art Club. Her work also appeared alongside that of Charles Payzant and Milford Zornes in several galleries and juried public art exhibitions at the Los Angeles City Hall, Whittier College, and the Greek Theater. When reporting on an exhibition, art critics of the day frequently singled out Rousseau's work.

By 1944, Rousseau had matured into an artist with numerous accolades and awards. However, Shirley Rousseau Murphy recalls that as her mother's technical competence increased, she felt constrained by those painting techniques in which she had been trained, which did not adequately bring alive the light and movement around her. Her daughter recalls that between 1945 and 1951, Rousseau "was reaching for a bolder, looser style. She wanted to infuse her work with the brilliance of color and light she responded to so powerfully. This was what she was exploring at that time, trying to direct a drive that wasn't yet satisfied."

Sausalito Boats #3

Sausalito Boats #3

Shirley Rousseau Murphy was a student at CSFA from 1947 to 1951. Shirley's stories about Park's bold new figurative work excited Helen so much that she returned to CSFA, enrolling in Park's portrait painting class in 1951. Rousseau had found her new direction. With Park's return to figure painting, he used his classes to articulate what he was attempting to do. "I could paint with more absorption, with more enthusiasm for the subject which would allow some of the aesthetic qualities, such as color and composition, to evolve more naturally. With subjects...I feel a natural development of the painting rather than a formal one," Park stated. To Rousseau, this was a revelation. Under Park, she made dramatic changes in her painting. She produced eight Park-like canvases that summer. Only when she returned home was she able to synthesize Parks admonishment to create a free, natural structure with her own vision of light and life in the landscape.

The loose painting style associated with Bay Area Figurative art enabled Rousseau to expose personal characteristics hidden in the tight compositions of her Modernist years. According to her daughter, she "was a basically innocent, shy person. Yet, she had an enthusiasm for life, a wonderment about the world around her." The summer spent with Park was so exciting to Rousseau that she felt re-energized as an artist, and the years from 1951 to 1968 would be her most productive and successful. After working under Park, she was able, at last, to combine the elements of light, figure, enthusiasm, and innocence that identified her persona. "She could hardly wait to get out and paint," remembers Shirley. "Mother often would be out of the house by 5 a.m. to get in a full day's work."

Carolyn Jones notes that Bay Area Figurative art merged the traditional and non-traditional, and "portrays physical attributes associated with California (deep, saturated colors and the play of strong sunlight) and often depicts pastoral or suburban subject matter." Rousseau's interpretation of the movement was an integration of her old and new styles. In the most apparent physical changes, the canvases became larger, her palette lightened from somber tones to vibrant reds, greens, pinks, yellows, and blues, vivid brushstrokes became essential elements of movement. And, as seen in Sausalito Boats #2 and Sausalito Boats #3, she merged figures with geometric landscapes.

Park's figurative work embraced concerns of character, style, composition, color, and subject matter. While Park articulated the need for representational subject matter as a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, Rousseau experienced the need for a different kind of break. She had embraced landscape and figure themes throughout her career, but under Park, Rousseau developed a unique simplicity in her interpretation and depiction of the human form.

In her post-1951 work, Rousseau's figures exhibit several immediate characteristics. They are primitive, faceless, handless, and convey the universality of timeless human activity in work, conversation, and purposeful action. Her figures capture innate innocence and optimism; activities become meaningful, human experiences because of their commonality. Sausalito Boats #1 exemplifies this new focus of Rousseau's work. This painting, which reveals the artist's delight with the Sausalito docks, was exhibited in the Santa Barbara Art Association's annual award show. She produced a number of these scenes in which she sought to unite the elements of light, primitivism, energy, innocence, and an enthusiasm for life. Here, brightly-clothed, simple figures and the brilliant boats on the water reveal the clear, dazzling day emerging after the customary morning fog. Rousseau does not attempt to convey a socially relevant scene; instead her work captures the essence and energy of human interaction with nature, of pleasure and work, of action and repose.

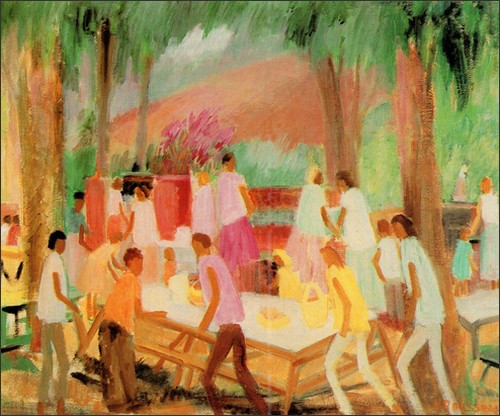

Picnic

Picnic

In addition to the new figurative emphasis, Rousseau welcomed the opportunity to experiment with light. Joachim Smith describes Northern Californian light as "less milky and the shadows less filmy [than Southern Californian light]. . . . Haze or smog is far less dense in Northern California, making shadows deeper and contrasts sharper." Capturing these characteristics of light in and around Mill Valley and Sausalito became a significant part of Rousseau's post-1951 work. In Picnic, Rousseau creates a circle of brilliant light as figures converge at the picnic tables. Light radiates from the tables and illuminates each figure.

Rousseau's unique figurative work resulted in regional recognition in the 1950s and 1960s. In addition to solo gallery shows throughout California, she was included in numerous exhibits ranging from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art to California Watercolor Society presentations at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Among other awards was the best show prize at the Sausalito Art Show in 1964, at which Rousseau was honored for Panama #2, completed on a trip to that country.

During 1963 and 1964 Rousseau lived with her daughter in Panama. There, they made daily sketching excursions to wharfs and marketplaces. Amidst pickpockets, buzzards, the smells of cooking food, heat, humidity, and political uprisings, Rousseau produced some of her most important work. Living in Panama offered Rousseau more opportunities to study light, color, and figures. The dazzling equatorial sunlight and striking black figures hauling bananas in Panama #2 indicate how captivated she was with her new environment. Shirley remembers how her mother worked almost non-stop while in Panama. Struck by uncharted territory, Rousseau sketched on-scene large pastels and spent the next day painting. Upon her return to the Bay Area in 1964, she continued to paint in the Figurative style. She moved to Santa Barbara in 1968 where she resided until her death in 1992..

Helen Rousseau was an accomplished Californian Modernist who found in Bay Area Figurative art new ways to advance her own style of painting. In relation to what Park and others sought in returning to figurative painting, Rousseau found a different kind of satisfaction. Her intrigue with figures, light, and color transcended her early training and blossomed after working with Park. In conjunction with Rousseau's Modernist training, the result is a singular contribution to the Bay Area Figurative era and Californian painting.

Sausalito #1

Sausalito #1

Awards, Exhibits, and Memberships

Awards

California Art Club annual, City Hall Tower, Los Angeles, 1960, first award, watercolor; also an honorable mention

Downey Museum of Art 1960 (or 1959)

Laguna Beach Art Association, two first awards, 1940s.

Las Vegas Annual, 1959, second award, watercolor, The River #2

Los Angeles Outdoor Art Festival, Barnsdall Park, 1950

Long Beach Art Association:

1939, second award

1943, first award oil; second award, portrait oil

1944, second award oil; third award, oil

1945, second award oil

Marin Society of Artists Annual 1962, The River #2

National Orange Show 1962 (or 1961), second award watercolor, untitled

Richmond Museum Watercolor Annual, 1962, The River #2

San Francisco Art Festival Purchase Award, 1962, Pink Sails

Sandpoint, Idaho, Bonner County Fair, 1948, first award

Santa Barbara Art Association, January 1971, honorable mention, acrylic

Santa Barbara Annual Awards Show, Santa Barbara Library Sausalito

Sausalito Women's Club Fourth Annual, 1964, Best of Show, Panama #2

Whittier Art Association:

19xx, third award

19xx, first honorable mention, Market Day

Women painters of the West:

Annual at Ojai Art Center, 1957

Annual at Whittier Art Gallery, 1958, honorable mention

Exhibits in 1959: three first awards, one of them for The Park

Exhibits in 1960: first award, Boats; honorable mention, Monkey Island

Juried Exhibits

Artist's Guild of Southern California Traveling Show, 1968-49, A Bright Sunday

California State Fair, 1956, 1959, 1960

California Water Color Society Annuals, 1958, 1960, 1961, including Los Angeles County Museum, Pasadena Museum, Long Beach Museum, California Palace of the Legion of Honor, Santa Barbara Museum.

California Water Color Society Drawing Show, 1960

California Water Color Society Oil Annual, 1960

California Water Color Society Traveling Exhibit, 1958-60: Mexican Institute of Cultural Relations, The Belles Artes, and Benjamin Franklin Library

Chico College Watercolor Invitational, February-March 1972, The Doorway; Sausalito

Downey Museum of Art 1960 (or 1959)

Ebell club, Los Angeles: 1942, Ranch; 1959, Ojai Valley

Laguna Beach Art Association: 1942, Summer Cottages; 1943, Imaginary; 1944, Dougan's Landing; 1951, Street Vendor; 1952, Street Corner; San Francisco; 1953, Norm's Landing; 1954, Mexican Village; 1957, Whittier Hills; 1957-58, High Noon.

Las Vegas Annual, 1959, 1960

Figures on deck of blue boat

Figures on deck of blue boat

Long Beach Art Association, 1939, 1943, 1944, 1945.

Los Angeles Art Association, 1960

Los Angeles County Museum Annual, 1961

Los Angeles County Museum, 1942

Los Angeles Outdoor Art Festival, Barnsdall Park, 1950

Los Angeles; Palos Verdes Estates, Palos Verdes, California.

Marin Society of Artists Art Bank ,1961 through about 1970

National Orange Show 1956, 1957, 1959, 1961, 1962,

Oakland Gallery (Museum?), 1932

Pasadena Art Museum Annuals, 1956, 1957, 1960

Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts, 1961

Philadelphia Watercolor Society, 1961

Richmond Museum Watercolor Annual, 1962

Sandpoint, Idaho, Bonner County Fair, 1948

San Francisco Art Association Art Bank, 1960, 1961, 1962, 1963

San Francisco Art Festival, 1962

San Francisco Art Institute Members Annual M. H. de Young Museum, 1962

San Francisco Art Institute Traveling Exhibit "Vistas," 1962-63: University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho; Rogue Valley Art Association Medford, Oregon; Erb Memorial Student Union, University of Oregon, Eugene; Indiana State College, Terre Haute; East Carolina College, Greenville, NC; Washington State University, Pullman, Washington; Pepperdine College,

San Francisco Museum Art Bank and Traveling Show, 1961, 1962, 1963

Santa Barbara Art Association, 1971, 1973, Raccoon Canyon

Sausalito Women's Club Fourth Annual, 1964

Tiburon First Annual Auction, 1961

Tucson Annual, 1960

Whittier Art Association

Women Painters of the West: Ojai Art Center, 1957; Annual at Whittier Art Gallery, 1958; 1959; 1960

.Gift

The Circus to Presbyterian Intercommunity Hospital, December 1959

One-Man Shows

Bakersfield

Golden Gateway Gallery, San Francisco, 1962

Institute Panemeño de Arte, 1964

Lafayette Hotel, Whittier, 1950

Long Beach Library

Montgomery Gallery, San Francisco, 2000 and 2004

Ojai Valley Art Center, 1960

Palos Verdes Library

Studio 15

Group Shows:

Ash Grove Gallery, Los Angeles, 3-man show, 1962

Jack Carr Gallery, 3-man show, South Pasadena 1959

Quey Gallery, Tiburon 1962

Invitationals

Ojai Valley Invitational, 1958

Was Sloan Invitational, Los Angeles 1958

Memberships

Artists Guild of Southern California

California Water Color Society

Long Beach Art Association

Marin Society of Artists

Oregon Society of Artists

Philadelphia Watercolor Society

San Francisco Art Association

San Francisco Women Artists

Santa Barbara Art Association

Santa Barbara Artists Workshop

Whittier Art Association

Some of the Paintings

of Helen Rousseau

Paintings: Northern CaliforniaPaintings: Sailboats

Paintings: Living in California

Paintings: Panama and Mexico

Paintings: Southern California

Paintings: 1940s and Earlier

Available paintings by Helen Rousseau

can be seen at

6th Avenue and San Carlos Street

P. O. Box 2953

Carmel-By-The-Sea, CA 93921

phone: (831) 626-1100

email: DMFA@DelMonteFineArt.com